|

6/28/2021 Trauma Survivor Kelly Hanwright Talks About Schizophrenia and her Survival Memoir The Locust YearsRead Now How did you become interested in the subject of mental health? I really got interested in mental health awareness after learning in therapy that my mother had untreated schizophrenia all of my life. My mom was diagnosed with a “hormone imbalance” in the 1950’s after experiencing a psychotic break in her teens. Always terrified of being institutionalized or being on any long-term medications, she refused to ever seek treatment. Some of my mother’s paranoid delusions were that my father was demon possessed, that random people were after us, and more. They were all terrifying. Once when I was about 10 or 11, she actually took us in the middle of the night to a preacher a few towns over who was supposed to be able to cast out demons. She didn’t even believe the preacher when he told her my dad was not possessed! Her illness also caused a lot of neglect. She would have these fits – I don’t know how to describe them exactly. She would scream and cry. Sometimes she would take all her clothes off and beat on herself. Then she would just go to bed. I remember opening cans of corn or eating cold hot dogs out of the fridge. But hey, at least there was food around. I learned to fend for myself in a hurry! Our house was always filthy and she never took a bath or shower. As I got older, she strongly discouraged me from bathing. When I finally decided bathing was important, I had to sneak and do it or I’d get yelled at. My neighbors gave me a toothbrush and a teacher taught me how to tie my shoes. Around age 8, my hair got so matted one time that I ended up having to get it cut really short. Personal hygiene was just not a thing for my mother at best, and at worst she almost seemed to fear it. What do you write? I dabble in a lot of things, but my main genre is poetry. My writing tends to explore my own mental health struggles and tries to share hope. I think I turn to poetry a lot because I’m a very visual thinker and it helps me express my feelings (not always an easy feat) when I can put them into the metaphors and imagery that poetry thrives on. I’ve found writing poetry very therapeutic and I highly recommend it to anyone who has been through any type of trauma. This year, I published my first book – a trauma and survival memoir called The Locust Years. Why do you write what you do? More than anything, I guess I’d say that I write for mental health awareness. It’s a topic that is very important. As a kid, and even as an adult reflecting on my experiences growing up with an untreated schizophrenic, which was a lot like growing up in an alternate reality, I felt extremely isolated. And it was impressed upon me from a very young age that there were all these secrets no one else could know about our day-to-day lives. The Locust Years started out as a collection of private poetry written in an attempt to process the traumatic experiences I’d been through including neglect, abuse, and the terrors of living in what felt like a daily war zone, as well as come to terms with my diagnosis of complex PTSD that those experiences caused. It dawned on me that even though it is a very private topic with a lot of embarrassing things intertwined, if I remained silent about my story I would actually reinforce the stigma that caused my mom to decide against seeking treatment! I look at my book, my blog, and what I post on my Facebook page as ways to be a mental health activist. My mom needed treatment – therapy… medicine... She needed love and support from the people around her. And I have to say that, looking back, I can trace the reactions of neighbors and supposed “friends” and realize they knew deep down something was wrong. But instead of trying to help, they turned a blind eye and avoided us. (My poem “Power of Neighbors” is about that.) Not only could I not contribute to that tradition, but I also knew I wanted to stand in solidarity with others and help break the stigma. Mental health is health! And it’s just as important as physical health. It’s high time we pay appropriate attention to it. We all have some type of mental health struggles. Lets just admit it and support each other! Follow Kelly on Facebook and Instagram, check out her blog at kellyhanwright.com and her survival memoir in poetry, The Locust Years. Please leave a review if you like it. It is Kelly’s sincere wish that you find it helpful in some way. <3

0 Comments

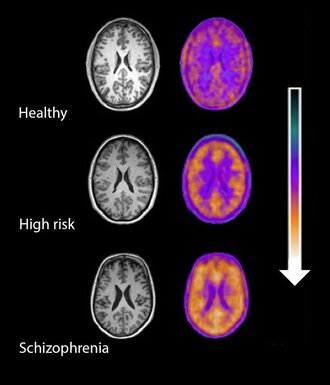

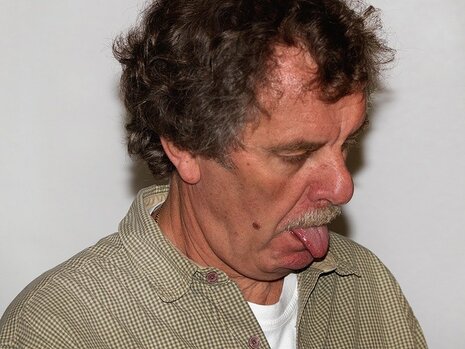

There is no cure for schizophrenia. But there is treatment. These treatments save lives, but the side effects can be hell. Last week we talked about what schizophrenia looks like when all of the symptoms are present. This week I’m going to talk about what a person with schizophrenia’s life looks like during the day-to-day. For a person with schizophrenia, taking medications every day is of utmost importance. The delusions from schizophrenia can be traced back to an over-release of the chemical dopamine in the brain. Anti-psychotics merely plug the leaky dopamine pipe. Once the leaking pipe is stopped, however, the person starts feeling much better and may decide they do not need their medications after all. Bad idea. The hallucinations and delusions come back with a vengeance (Lewis). But there’s another problem with the dopamine suppressing drugs: they don’t target just the areas where the delusions originate, but also the rest of the brain. And what’s another disease associated with low dopamine? Parkinson’s Disease. A person taking these anti-psychotic medications can not develop actual Parkinson’s Disease from the drugs, but may have pseudoparkinsonism with similar symptoms such as a hand tremor, issues with balance, and difficulty walking. They develop a shuffling gait, mask-like face (a decrease in ability to show expressions on their face due to paralyzed facial muscles), muscle stiffness, drooling, slowness in starting movement. The person taking the medications may experience dystonic reactions where spasms occur in discrete muscle groups such as the eyes and neck (the patient will have chronically raised shoulders like a tortoise shell). They might have a protruding tongue, difficulty swallowing, and spasms around their throat which, if bad enough, might lead to a compromised airway. This is obviously terrifying. Most of these side effects develop shortly after starting or increasing the dose of medications. A more long-term side effect, however, is tardive dyskinesia. It’s characterized by “abnormal, involuntary movements such as lip smacking, tongue protusion, chewing, blinking, grimacing, and strange movements of the limbs and feet” (Videbeck). Keep in mind the person is fully aware of the strange movements and are probably embarrassed. This bizarre, uncontrollable behavior may lead to further social isolation. Is it really a wonder they want to come off their meds? And in all this, the anti-psychotics are only treating half of the problem. In the previous post, I mentioned positive and negative symptoms. Positive symptoms are those symptoms that are added experiences to a ‘normal person’: hallucinations, delusions, etc. Negative symptoms are things such as depression, withdrawal, loss of joy, etc. Anti-psychotics do not treat the negative symptoms. The struggle of day-to-day living for a person with schizophrenia is enormous. Because of this, pharmacology is just one part of the treatment. Individual and group therapy is key. There, things such as family dilemmas and medication management can be addressed. Clients can undergo social skills training where complex social behavior is broken down into easier to manage parts. Some very creative people have put together environmental supports such as signs, calendars, hygiene supplies, and pill containers to cue clients to perform various tasks. If a schizophrenic person has a good support system, they have a better shot than most. Family education and therapy are known to diminish the negative effects of schizophrenia and reduce the relapse rate. Unfortunately, good support systems are hard to build and even harder to sustain. It’s hard to take care of someone who believes everyone is out to get them. Or to be patient with someone who offers very little in return: no smiles, flat expressions, lack of joy. Unfortunately, this is a part of the therapy that is forgotten about the most. So take all that together for a moment and imagine life as someone with schizophrenia or a caregiver of someone with this disease. I’m going to give you a quick example from the perspective of a writer: Hunter moved into the apartment down the hall from his parents. He’s super excited to be independent and have a place of his own. For the past several years since his diagnosis, Hunter’s routine has been the same: get up, get dressed, brush teeth, etc. all in the same order every day. Unfortunately, just as he is about to take his medications, someone knocks on the door. It’s the maintenance guy just stopping by to let Hunter know the power might go out for a few minutes later that day. But it’s enough to distract Hunter and he forgets the meds. He goes on, grabs his bus pass, and goes to work at the deli. While he’s at the bus stop, people keep staring at Hunter. He tries to ignore it, as he leans back in his seat smacking his lips and wipes a bit of drool from the corner of his mouth. Hunter gets to work on time, but finds Ricky working that day. Ricky laughs aloud at Hunter’s slippers. Apparently, he forgot to change his shoes too. All day, Ricky mocks Hunter’s slow movements, his shaky hands—just whatever he can to get under Hunter’s skin. But that’s not the worst of it. Hunter is used to Ricky, but the customers start whispering about him behind his back too. And then there’s one guy that’s watching Hunter just a little too closely. Later on that day, Hunter sees the guy across the street, watching him through the window. Hunter takes the bus home, and all the people are watching him now, talking about him. He sees the guys again outside the bus window. Now Hunter knows he’s being followed. When Hunter gets home, he locks the door and goes to kitchen. He grabs a meat hammer and sits by the window where he’s sure he hears the man outside, talking about him. The man says he’s going to get Hunter. He’s going to burn the apartment complex down and kill him and his parents. Hunter runs out of the apartment, not wanting to be trapped inside a burning building.

Later, his mom stops by and can’t find Hunter although his coat and wallet are inside. She searches the apartment complex and finally finds Hunter barefooted and hiding behind a dumpster. By now the voices have grown too loud. Hunter doesn’t recognize his mother and charges her with the meat hammer. A neighbor stops Hunter and restrains him until the ambulance can arrive, but Hunter is institutionalized until they can get his delusions under control. Unfortunately, this is the third hospitalization this year, and Hunter loses his job at the deli. Without the extra income, he has to move back into his parent’s apartment and start over. All because the maintenance guy stopped by. People with schizophrenia are just that: people. I hope this information has helped you gain a better understanding of the condition so that we can portray those effected by mental illness accurately. Sources: Psychiatric-Mental Health Nursing, by Sheila L. Videbeck, fifth ed., Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011. Lewis, J. (2011, March 6). The Future of Schizophrenia. Dr. Jack Lewis. http://www.drjack.co.uk/the-future-of-schizophrenia-by-dr-jack-lewis Last week I covered what schizophrenia looks using real-world experiences. This week, I’m going to dive into the disease on a more technical level. As per usual, none of this information is to be used to diagnose or treat anyone, but as a tool for writers to create characters who are close to life as possible and not mere caricatures of mental illness. Life with schizophrenia is hard for the person experiencing the symptoms as well as the family providing care. But consider this, there was only one treatment plan for schizophrenia 100 years ago: institutionalization. Although institutionalization is still part of treatment, it is often not the only part. Thanks to new treatments and medications, many people with schizophrenia live at home or in group homes in the community. Some even have jobs. I’ll be the first to say that mental health has a LONG way to go, but I believe it is important to keep in mind where we came from.  A person with schizophrenia may manifest the following (Videbeck p. 252):

The above list are considered “Positive Symptoms” as in they are added to the person. Most positive symptoms are treatable, but there are “Negative Symptoms” or symptoms that seem to be lacking in a person that generally linger after the positive symptoms abate. These are them:

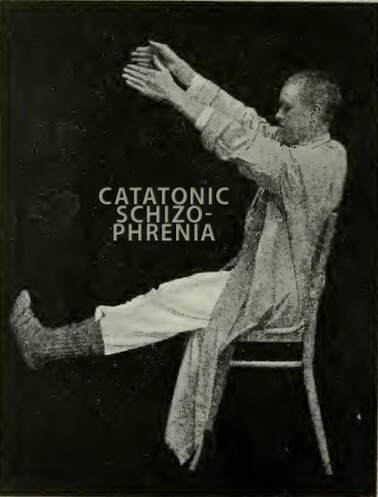

Keep in mind that the person experiencing these bizarre behaviors or thinking patterns may be fully aware of them. I once entered a patient’s room to find her smashing invisible bugs on her bedside table. She told me she knew the bugs weren’t real, but smashing them made her feel better. The extent of the awareness of symptoms is difficult to know since there is a huge communication barrier in many schizophrenic patients. The number of delusions, hallucinations, and their strength are all difficult barriers to break through. Not every person with schizophrenia will have all of the above symptoms. In fact, schizophrenia is less of a single illness and more of a syndrome. Here are the five major types according to the DSM-IV-TR:

While there can be a sudden onset of schizophrenia, most people generally develop signs and symptoms slowly over time. It starts with social withdrawal, unusual behavior, loss of interest in school or work, and neglected hygiene. Generally, the diagnosis is made when delusions, hallucinations, and disordered thinking begin to appear. The age at which schizophrenia appears often determines the overall impact of the illness. The younger the onset, the worse they tend to do. Also, a slower onset predicts a worse outcome than a sudden onset. Two years after initial onset, two patterns typically emerge. Either the person continues to experience psychosis and never fully recover (although symptoms may shift in severity over time), or they alternate between episodes of psychosis and near complete recovery. The intensity of the psychosis also seems to diminish with age. Some may be able to function, live independently, and succeed at jobs with stable expectations and supportive work environments. Most, however, have severe difficulty functioning in their communities. It is important to keep in mind that a person showing initial signs and symptoms of schizophrenia might lose all symptoms within a period of six months. This is called Schizophreniform disorder. Others might experience a brief psychotic disorder where delusions, hallucinations, or disorganized speech may last from 1 day to 1 month. It may or may not have an identifiable stressor or follow childbirth. There is SOOOOOO much to tell when it comes to schizophrenia and this post has already become way to long. Next week, I’ll be creating a post that brings together all of this information in a usable form. As I was researching this, I came across this article I found very informative but did not use as a source: http://www.drjack.co.uk/the-future-of-schizophrenia-by-dr-jack-lewis/ Psychiatric-Mental Health Nursing, by Sheila L. Videbeck, fifth ed., Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011. The half-moon serrated teeth of the knife gleamed in the overhead light. One quick jab and— “Get out! Get out!” Michael pounded his fists against his head, and Randy, his son, jumped in his seat at the kitchen table. A pencil fell from Randy’s hand clattering onto the half-filled math sheets. The numbers, if only he could decipher the numbers. The boy is hiding them from you. Michael’s fingers brushed across the cool metal. At the sight of the blade, in his hand Michael retreated, chest heaving. It won’t even hurt. You’ll make it quick. But it must done or— Michael ripped the blade from the counter and rushed for the front door. Barefooted, he stepped into his lawn, barely noticing cold snow. “Hey Michael!” Louis next door waved at him, a paper sack of groceries in hand. Michael fell to his knees, studying the blade bouncing light from the setting sun. The voice continued to call to him, telling him what to do. Michael pressed the blade against his arm and pulled. His teeth clenched as the skin tore. “Oh my god! Michael!” Louis dropped his groceries to the porch. “Michael, what are you doing?!” “I will not hurt my son!” Michael snarled as blood dripped into the snow.

I was initially going to crack open my textbook like usual and tell you all the ‘official’ things about schizophrenia, but I’m going to put that off until next week. Instead, I’m going to tell you what I’ve seen from my nursing practice. My first up-close encounter with schizophrenia in the clinical setting was with Mary*. Mary was a well-known frequent flier of the psychiatric institute I was completing my nursing clinical hours in. I was given Mary’s file to read then sent to speak with her for an hour. Since my previous vision of schizophrenia was of homeless people walking talking to the air, I was quite nervous about even approaching Mary, let alone sitting in the drab stone-walled courtyard on a bench and chatting. Mary, however, acknowledged me with a courteous nod. She never smiled at me, but she was never hostile or aggressive toward me. Instead, she talked about her life as I would expect anyone too, with earnestness about her life experiences. She had no verbal slurring or strange repetition of words. I could have walked up to this woman at Walmart and never known she was schizophrenic. Mary told me all about her conniving sister who was hell-bent on destroying her life. If Mary had a chance at getting a job, her sister would call the manager and convince him not to hire her. When Mary tried to move away, her sister followed her to the next state over and continued to keep her under her thumb.  Even while she was being institutionalized, her sister was stealing her social security check and paying the people inside to watch her. And the people here—oh she’d tell you about them. Everything you ate or drank was laced in parasites that would eat you from the inside out. The pills were laced too, which was why she was refusing to take hers. Of course, very little of this (if any) was true. But Mary believed it was. Because everyone was out to get her, she had no hope of securing a good job, good employment, or establishing any lasting relationships in her life. The next week, I met Todd*, a 20-year-old schizophrenic who, per the staff, had been practically abandoned in the institution by his family. Todd was heavily medicated when I met him. His posture was stooped, his speech was slurred, and his reaction time was comically slow. I asked him about his life, and my heart broke. Todd had accepted his diagnosis and knew he was mentally ill, but with this knowledge came the fact he would never be able to have a family or a real relationship of any kind. Or have sex. When he said this last part, he slapped his hand over his mouth—with exaggerated slowness due to the meds. It would have been funny had it not been sad and possibly true. He drew me a picture before I left. The drawing was the skill of a 3rd grader in markers. I still have it. Then we have Johnnie*. Johnnie was a patient of mine at the hospital. He came in for a bacterial gut infection which we treated in half a week, but while he was in our care, the psychiatric hospital discharged him. Getting an empty bed in a psychiatric hospital is nearly impossible, but Johnnie was so unwell we could not discharge him to the streets either.  Hospitals are not designed for long-term care of anyone, especially psych patients. Johnnie would walk down the hall outside his room and bang his head against the walls. Because of this, he was forced to stay in his room the whole time. Johnnie would scream and wail so loud you could hear him throughout the whole floor. Patients would complain, but what could we do? He would try to hit nurses and fight. He jammed his hand into his mouth and bit until it drew blood. We tried to place him in an institution somewhere—anywhere, but no one would take him. I don’t know how many combinations of medications we tried, but we couldn’t find the right balance to keep him calm. So what was the solution? Johnnie was tied to his bed. Still screaming, still fighting. His wrists became sores from pulling against the restraints. He stayed in the hospital like that for a month. Johnnie was pretty much non-communicative, but we can imagine his thoughts knowing how Mary thought. He thought we were trying to kill him, so we tied him to a bed. That helped. Johnnie was just a little older than Todd. Similar dreams, similar hopes—like all of us, but this was his life. Terrified, trapped, and being harmed by the people who should be helping him. Our system is broken. And so is our view of mental illness. Yes, schizophrenics commit violent crimes more often than the general population, but they are victims of crimes more often too. What if someone raped Mary? She could report it, but would anyone believe her? What if someone beat up Todd? He could report it, but would someone think it was self-inflicted? I don’t know what to do about our broken system. But I do know, as writers, we have a responsibility to portray characters accurately. So, think on this before you write a schizophrenic character. Are they flat and cartoon-like? Or do they have hopes, loves, and broken dreams as well? *names changed |

Details

AuthorRW Hague is a registered nurse with over eight years of experience within the medical field. Using her medical expertise, she writes stories that are gritty and compelling. Archives

November 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed